Vaquita Porpoises May Go Extinct in 2022

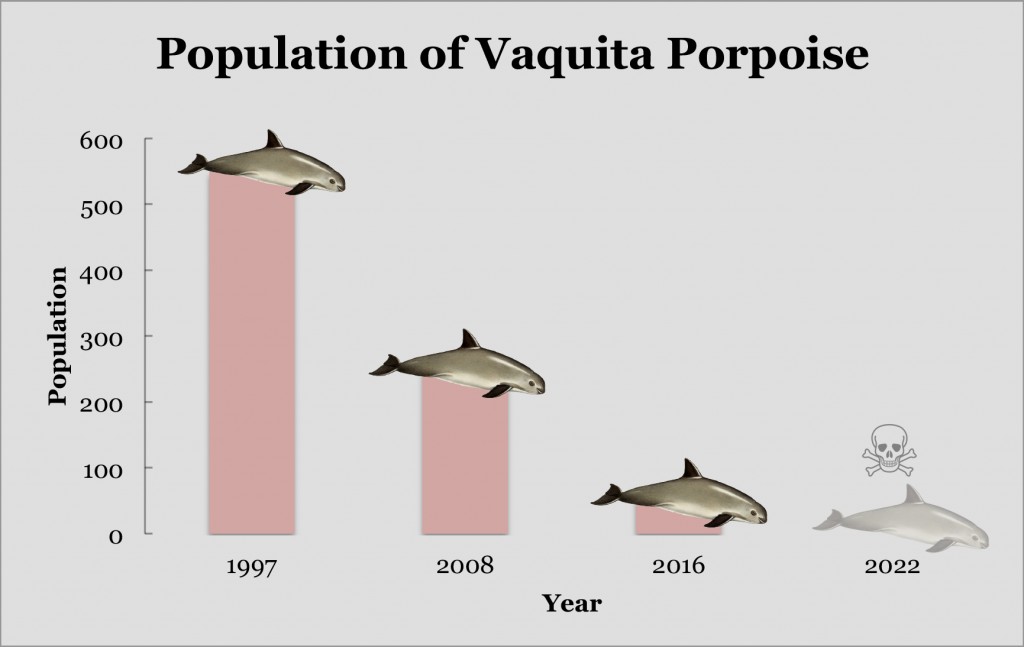

The world’s rarest marine mammal has found itself becoming rarer and rarer each year. Now, according to a report presented this month to Mexico’s Minister of the Environment and Natural Resources and the Governor of Baja California, only 60 vaquitas remain in the Gulf of California – representing a decline of more than 92 percent since 1997.

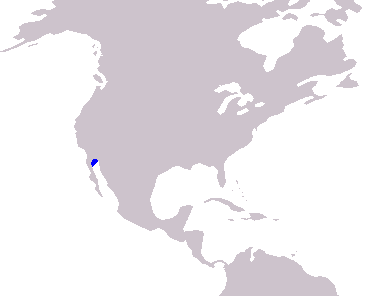

Vaquita porpoises are endemic to this small area highlighted blue. © Wikimedia Commons

Vaquita porpoises, Phocoena sinus, are found only in the upper area of Mexico’s Gulf of California (Sea of Cortez), a body of water squeezed in between Baja California Peninsula and the Mexican mainland. The world’s smallest porpoise was only discovered in 1958 and a little over half a century later, they are on the brink of extinction.

Causes

In 2015 there appeared a sign of hope for the porpoise, when the Mexican government imposed an emergency ban on gill-net fishing and pledged to invest US$36 million each year to support affected fishing communities. Gill-net fishing is a common method used by commercial and artisanal fishermen – in the Sea of Cortez it is used to catch totoaba, a formerly abundant marine fish that is itself critically endangered. Vaquita end up as by-catch in the nets and become entrapped, where they suffocate and drown. According to the Environmental Investigation Agency, in the past three years, half of the vaquita population has been killed in gill nets.

We spoke to Lorenzo Rojas-Bracho, Chairman of the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA), who stated that there were no other threats facing vaquita porpoises, but for gill nets.

“Again the risk factor is incidental mortality,” Lorenzo said during the interview. “We ran a risk factor analysis and found that no other factor has been affecting vaquita over the years.”

There is a high demand for totoaba swim bladders; according to the New York Times they can sell for as much as US$10,000 a kilogram in China and Hong Kong, where it is considered a delicacy and is claimed to hold medicinal benefits. With such a demand and high price, it is unlikely that this illegal fishing practice will die down quickly without stronger enforcement from governing bodies.

Protection

Frustrating Lorenzo and his team is the fact that “years of management and conservation plans have not fully worked because none of it has tackled the main factor: to eliminate gill nets and reduce by-catch to zero”.

“There have been good attempts that probably slowed the decline,” he said, “but not enough to stop it and even less to reverse it.”

Upon asking whether there were any future plans in place to try and regrow the tiny vaquita population, he simply stated, “ban gill nets in the upper Gulf of California – that is the only chance for the vaquita.”

Showing the decline of the vaquita porpoise over the years, and the estimation of their extinction in 2022

Urgent and coordinated action to stop the illegal fishing, trafficking and consumption of totoaba is needed from Mexico, the United States and China. Without any nets, there is no chance of vaquita ending up as by-catch.

It is unconfirmed whether other marine creatures are in similar danger of extinction, although the global decline of fish catches, combined with rising demand, is leading to a global fisheries crisis that threatens the Gulf of California ecosystem as well as nearly six million people who depend on fish for sustenance and their livelihoods. The Gulf alone is the source of nearly 75 percent of Mexico’s total annual fish catch, but overfishing (both industrial and artisanal) is now blamed for dramatic declines in many marine creatures, including cetaceans, sharks, rays and other fish stocks.

The future

It is uncertain what lies in the future for the vaquita porpoise, and if it is to disappear, what the effect will be on its surrounding ecosystem. Much like the Caribbean monk seal, which is now recorded as extinct, and the endangered Maui’s dolphin, which clings desperately to survival off the coast of New Zealand, these marine mammals that operate in small native ranges appear to be the most effected by overfishing and changes to the underwater environment.

“If the emergency two-year gill-net ban is lifted, [as it is planned to be] in 2017, vaquitas could go extinct in only five years,” surmised Lorenzo.

As yet another marine species teeters on the brink of extinction, it seems clear that greater protective measures must be put in place – and fast. But with the ongoing threats of the El Niño phenomenon and human impacts such as oil drilling and overfishing, it is apparent that many once-pristine and thriving marine environments are being irreparably altered.