Incredible Stories of Seahorses

This article originally featured in Asian Diver Big Blue Book (Issue 2/2016), text by Helen Scales.

Until you see one for yourself, it’s easy to believe that seahorses are pure make-believe. So curious, so magical, they seem to have wandered straight out of a book of fairy tales. Even a dead, dried seahorse washed up on a beach keeps its otherworldly shape, encased in its enduring bony armour, waiting for someone to come along, pick it up and wonder what it might be. A miniature dragon? An enchanted serpent? It’s no wonder seahorses have been puzzling people around the world for centuries, inspiring them to tell stories, pass on myths and legends, and find mystical uses for these most charming sea creatures.

A statue of the Roman god Neptune with a seahorse © mmorell

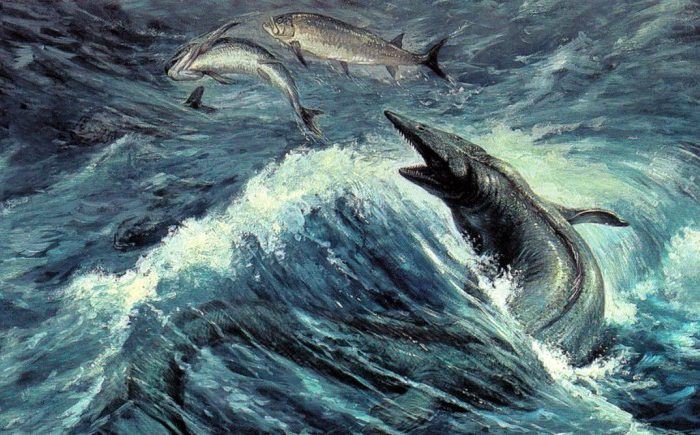

Some of the oldest seahorse stories tell of the Greek sea god Poseidon galloping through the oceans on a golden chariot pulled by hippocampus, the beast that was half horse and half fish (today, the seahorses’ scientific name also happens to be Hippocampus). It’s thought ancient Greek fishermen believed the real seahorses they sometimes found tangled in their nets were the offspring of Poseidon’s mighty steeds.

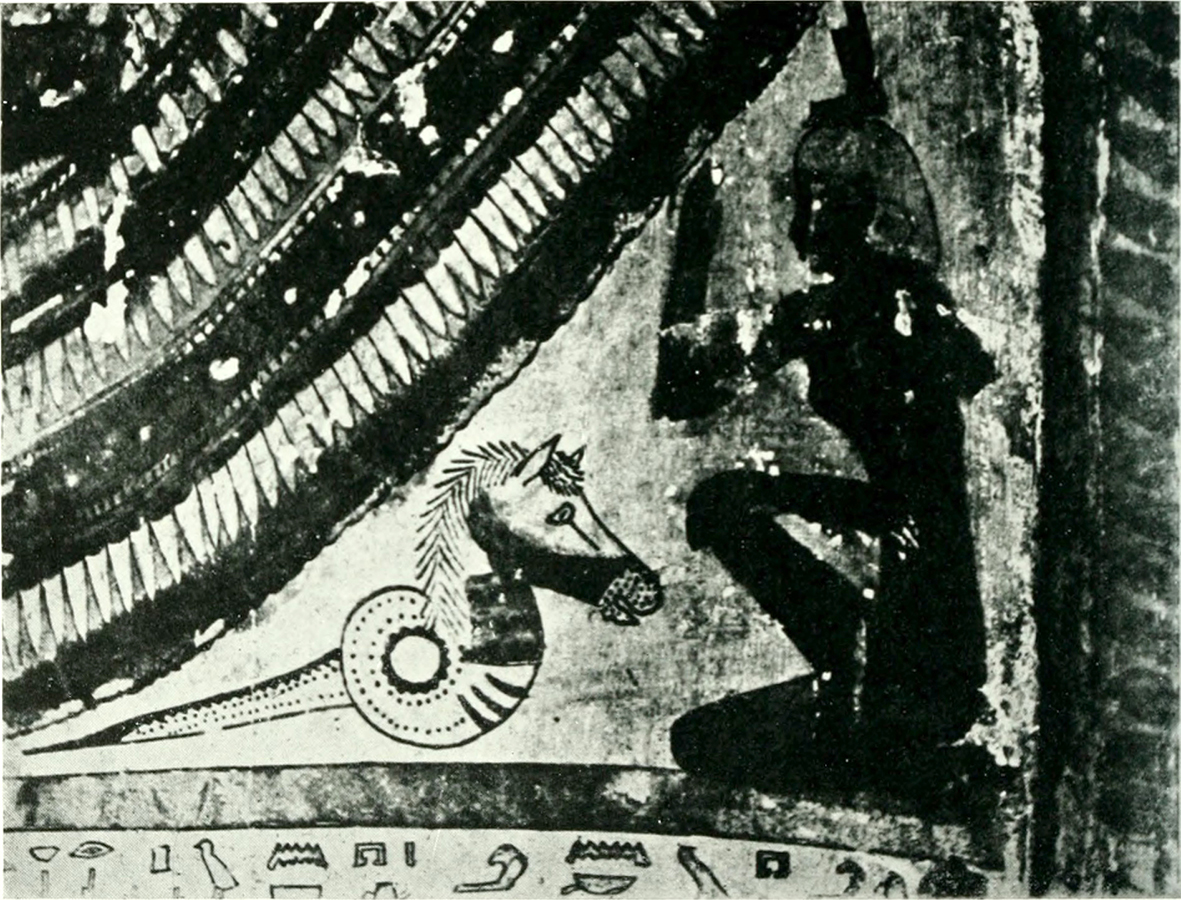

All sorts of ancient Mediterranean art and objects depict the hippocampus. Phoenicians and Etruscans often painted these watery horses on the walls of burial chambers, accompanying the dead on their voyage across the seas and into the afterlife. There’s even a single hippocampus from ancient Egypt painted on a mummy’s coffin.

Many other legends tell stories of watery spirits that take the form of horses. Scottish lochs are said to be haunted by “kelpies”. They come onto dry land and graze with other, normal horses but if you mount and ride one you’ll be dragged underwater as your steed tries to drown and eat you. Similar malevolent beasts were called “tangies” in the Orkney Isles and “shoopiltrees” in the Shetlands. Scandinavian legends tell of the “havhest”, a huge sea serpent, half horse and half fish like hippocampus, that could breathe fire and sink ships.

Ancient Greek and then Roman myths about hippocampus spilled over into matters more medical. In the first century, Roman writer Dioscorides compiled a book of herbal medicines that were widely used at the time. Among the many ingredients he listed is the seahorse which, he claimed, can be mixed with goose fat and smeared on a balding scalp to restore a full head of hair. Pliny the Elder also advocated the therapeutic use of seahorses, listing them as cures for leprosy, urinary incontinence and fever. Yet another Roman writer, Aelian, claimed that seahorses could cure a bite from a rabid dog by counteracting the hydrophobia induced by rabies; eat a seahorse, Aelian said, and you’ll spend the rest of your life drawn inexorably to the soothing sound of babbling rivers and streams. Be warned though: He also wrote that a seahorse boiled in wine is a deadly poison.

Decorative painting of the hippocampus, from the interior of an Egyptian mummy case dating from the 26th dynasty (700–500 B.C. © The American Museum Journal/ Wikimedia Commons

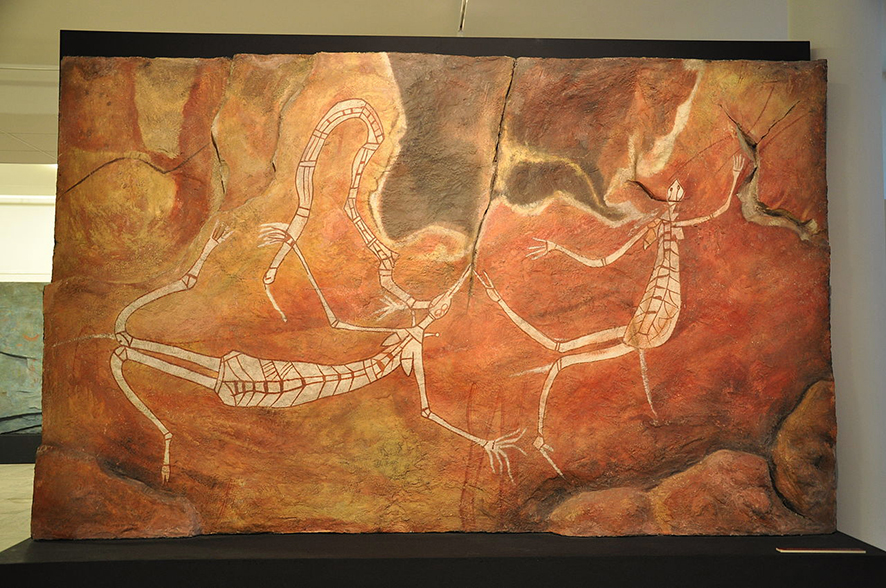

Elsewhere in the world, other early cultures seemed to have been aware of seahorses. Aboriginal Australian rock art, from as long as 6,000 years ago, depicts a revered Dreamtime ancestral spirit called the Rainbow Serpent. As Dreamtime legend has it, the Rainbow Serpent emerged from the earth long ago and wandered about, sculpting the landscape into mountains, rivers, and gorges. The depiction of these creator spirits varies through time and from place to place across Australia, but archaeologists have noted the similarity between some Rainbow Serpents and a close relative of seahorses called the ribboned pipefish. One particular drawing, found in the north of Australia in 1993, has a distinctive down-turned snout and long, narrow body, covered in weedy filaments, that all-in-all seems a good fit for the seahorses’ cousin.

On the other side of the globe another ancient group of people were putting seahorses in their artwork. Not a lot is known about the Picts of Scotland but among the few Pictish artefacts that survive today are intricately carved stones, made in the seventh century, including some depicting animals with a horse’s head and fish’s tail. They appear to be stylised versions of the Roman hippocampus. Other stones show more lifelike creatures with no legs and a coiled tail. Some archaeologists think these might have represented real seahorses, a stretch of the imagination perhaps, but even today seahorses do occasionally show up on the chilly shores of far northern Scotland.

An illustration of the mythical Scottish “kelpie” © insima

In distinctly warmer waters, on the shores of the Gulf of California, an ancient Mexican tribe called the Seri tells a legend of how seahorses came to be. Long ago, when the world was new and all the animals talked and wore clothes, there was a seahorse who lived on Tiburon Island. Back then the seahorse was a fat, well-fed fellow and also something of a prankster. Having committed some untold wrongdoing, the seahorse incurred the wrath of all the other animals who chased him, throwing rocks and stones. He fled to the beach and, with nowhere to run, tucked his sandals into his belt and dived into the sea, never to return. To this day, the ocean-bound seahorses are scrawny and thin, after their ancestor was flayed by the other animals, and where his shoes once were is now a little fin.

Beliefs in the magical and mystical powers of seahorses continue today. Fishing communities in Malaysia and the Philippines hang dried seahorses about their homes as talismans to dispel evil spirits. In Indonesia and Mexico, seahorses are used to protect money and bring prosperity. On the Indian Ocean island of Zanzibar, fishermen sometimes burn seahorses and sprinkle the ashes over fishing nets to bring good fortune and lure in more fishes.

Like in Roman times, seahorses are also still used as folkloric medicines around the world. In India, dried seahorses mixed with honey are used to treat whooping cough; in Indonesia seahorses are used in Jamu medicine to treat rheumatism, memory loss and impotence; Vietnamese fishermen soak seahorses in bottles of vodka, which they sip to give them strength during long trips at sea; in Latin America they are used to treat asthma; and in Japanese Kanpo medicine, seahorses are valued as an aphrodisiac.

Australian Aboriginal art depicting Namaroto spirits and the Rainbow Serpent Burlung (Borlung) © HTO/ Wikimedia Commones< /i>

Without doubt, though, the strongest beliefs in seahorses persist in China. For centuries seahorses have been used as an ingredient in traditional Chinese medicine. There’s a long list of conditions that seahorses are prescribed for, ranging from a sore throat, to incontinence, broken bones or, once again, a flagging sex drive. There are even texts describing a magical preparation of seahorse, mixed with spiders, that allow people to breathe underwater.

Although beliefs surrounding the therapeutic benefits of seahorses are rooted deep in the past, they are having a very real impact in the 21st century. Demand for seahorses in traditional Chinese medicine is growing like never before and wild seahorses are being targeted all across the globe. Each year, millions of seahorses are caught and sold to the medicine trade. Conservation groups are working hard to make seahorse fishing more sustainable and campaigners are trying to persuade people to seek alternatives to these expensive and endangered ingredients. Because if we’re not careful, there’s a very real possibility that seahorses could become so rare and hard to find that all we’ll have left are those magical stories and fairy tales.

Dr Helen Scales is a freelance writer, documentary-maker and marine biologist based in Cambridge, England. A keen scuba diver and freediver, she spends as much time as she can beneath the waves, researching stories that connect people and wildlife. She’s made documentaries exploring the intricacies of sharks’ minds and the dream of living underwater, and is currently writing a book about the wonders of fishes. She is the author of one of the world’s most authoritative books on the history of our relationship with the seahorse, Poseidon’s Steed, and her latest book, Spirals in Time, has just been released. Both are available online via Amazon and Open Trolley, and in Singapore at Kinokuniya.

Dr Helen Scales is a freelance writer, documentary-maker and marine biologist based in Cambridge, England. A keen scuba diver and freediver, she spends as much time as she can beneath the waves, researching stories that connect people and wildlife. She’s made documentaries exploring the intricacies of sharks’ minds and the dream of living underwater, and is currently writing a book about the wonders of fishes. She is the author of one of the world’s most authoritative books on the history of our relationship with the seahorse, Poseidon’s Steed, and her latest book, Spirals in Time, has just been released. Both are available online via Amazon and Open Trolley, and in Singapore at Kinokuniya.