Project Tektite: The Aquanauts That Lived in the Sea

One of the greatest, and most dangerous, programmes of its time, the Tektite project was the USA’s first nationally sponsored scientists-in-the-sea scheme. A cooperative government-industry-university effort that took place in Lameshur Bay, Virgin Islands (1969-70), it attracted some of the big names of the diving industry, from Sylvia Earle to Ed Clifton, to go and reside below the waves for around 60 days.

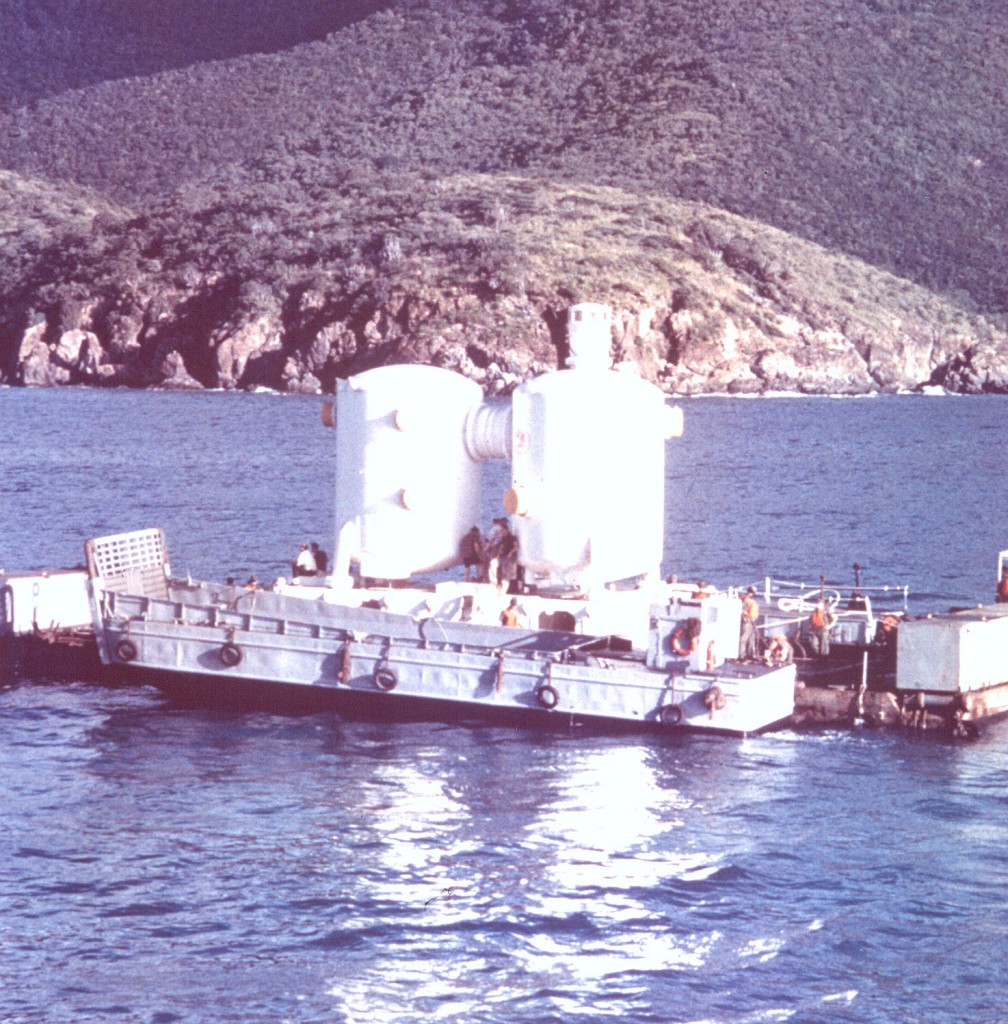

The Tektite habitat before being deployed © Wikimedia Commons, from NOAA Photo Library

As nationally sponsored programmes, there were two projects conducted – Tektite I and II. The Office of Naval Research coordinated Tektite I; the Department of the Interior, Tektite II. Scientists were selected as Tektite aquanauts primarily on the basis of research proposals submitted, and secondarily on the basis of health and diving skills. In Tektite I, four men lived in the Tektite habitat for 60 days, while Tektite II comprised of 10 missions lasting 10-20 days with four scientists and an engineer on each mission. The famous “Mission 6” was historic in that it was the first team of women to conduct research of this type in the world – it effectively shifted the patriarchal structure of ocean exploration and paved the way for many more female explorers.

Living Underwater

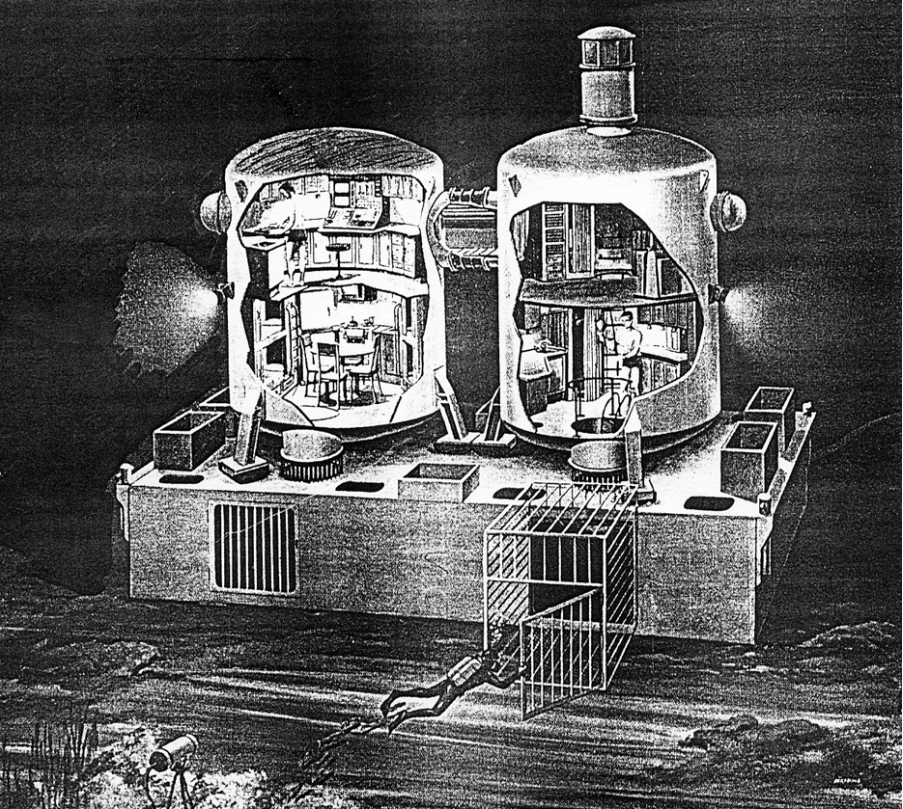

Looking like two sunken silos, the Tektite habitat was designed and constructed by the General Electric Company. On the exterior, there were two white metal cylinders four metres in diameter, six metres high, joined by a flexible tunnel and seated on a rectangular base in 15 metres of water. To get air, water and electric power, multiple cords extended from the habitat to the shore, and sewage was deposited by a pipe 300 metres away to a site 22 metres deep.

A clear example of hell for anybody who is claustrophobic, each cylinder housed two rooms – meaning four in total. The main entrance was in the floor of the “wet room”, a laboratory and storeroom for scientific and diving equipment. A ladder led down into the sea through an open well, and pressure was maintained at 2.5 atm, sufficient to keep water from rising through the entry well. These wet rooms were ideal for pre- and post-diving operations but also housed typical topside items such as a clothes dryer and a hot freshwater shower. Keeping things compact, above the wet room was the engine room, containing essential life-support systems, a freezer for food storage, and a small but private bathroom with sink and toilet.

To access the “third room”, referred to as the control room or bridge, the scientists had to cross through the tiny tunnel connecting the two cylinders. To communicate with the world above, the room contained communications and monitoring systems, and to make complete use of space, a dry laboratory, and library. It was the primary domain of the habitat engineer, who even slept there on a folding cot.

Cutaway view of the Tektite habitat showing arrangements of the four rooms. Image courtesy of Smithsonian Institution

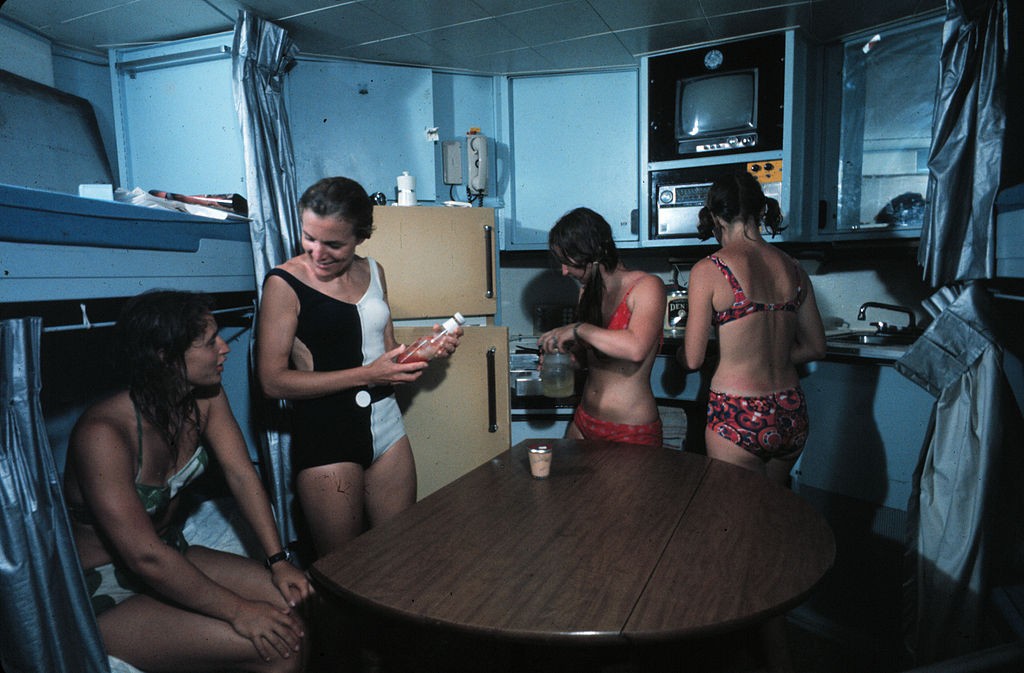

The habitat did a good job of making the scientists forget that they were totally submerged by hundreds of gallons of water, with carpeted floors, television and controlled temperature and humidity. The bottom left room was the crew quarters, including four built-in bunks with draw curtains, and personal storage drawers filled two sides of the room. There was also a refrigerator, stove, sink, and storage cupboards – and they were able to dine at a table in the centre of the room.

The only reminders of them being so far away from civilisation and the topside world was the emergency escape hatches located in the two bottom rooms, and the hemispherical ports allowing the scientists to gaze out at the reefs, but which also acted as a stark reminder of how deep and alone they really were.

The “Mission 6” aquanauts in the bedroom-cum-kitchen-cum-dining room of the habitat © Wikimedia Commons, from NOAA Photo Library

Lameshur Bay

The bay was chosen as the site for the programme due to a number of favourable characteristics. As it is within the Virgin Islands National Park, it was a relatively undisturbed area with a variety of plant and animal life inhabiting the various coral reefs, seagrass beds and sandy plains. Living in this diverse underwater world allowed scientists to get closer to, and stay longer with, the marine life – gathering information on diurnal (daytime) and nocturnal behaviour. They had more time to make observations, and the time that was available for productive research in the water, day after day, exceeded that previously experienced by any of the aquanauts.

Research

One goal of the programme was to show that saturation diving from an underwater laboratory could be done efficiently, safely, and at a relatively small cost. These selected pioneering scientists were journeying into dangerous, unchartered lands and active research techniques such as these had not been used before.

Nine studies conducted during Tektite I and II dealt with some aspect of coral reef ecology. Many of the studies are still being continued – and more relevant than ever – to this day: bio-acoustic studies on reef organisms, such as parrotfishes and groupers; influence of herbivores on the marine plants of the location; patterns of behaviour of coral reef fishes, looking into the times that diurnal fish species awoke. It was an incredibly exciting time for ocean exploration.

Sylvia Earle displays samples of the reef to an aquanaut inside the Tektite habitat © Wikimedia Commons, from NOAA Photo Library

During the course of the project, over 60 scientists and engineers lived and worked beneath the sea. Working simultaneously on land were teams of scientists, professors, students and other participants observing and studying the aquanauts. The project was a success and helped NASA to understand how astronauts could work in completely isolated and confined areas. An intriguing preview of what future life could be like, with perhaps many inhabiting the world’s oceans in such sub-aqua habitats, Tektite I and II could be described as ahead of its time.