Saving the Sharks of the Shark Triangle

By: Randall Arauz, Fins Attached Marine Research and Conservation International Marine Conservation Policy Advisor

Few places on Earth rival the spectacular biodiversity and abundance of highly migratory marine megafauna of the Eastern Tropical Pacific. For quite a while now, it has been known that these highly migratory species are not randomly distributed throughout the ocean, but rather, form aggregations at three specific oceanic islands during their adult life stage: Cocos Island, Costa Rica; Malpelo Island, Colombia; and Galápagos Islands, Ecuador. Parades of silky sharks and Galápagos sharks, aggregations of hundreds of hammerhead sharks, whale sharks, and tiger sharks are all common inhabitants of these remote islands that form the Shark Triangle.

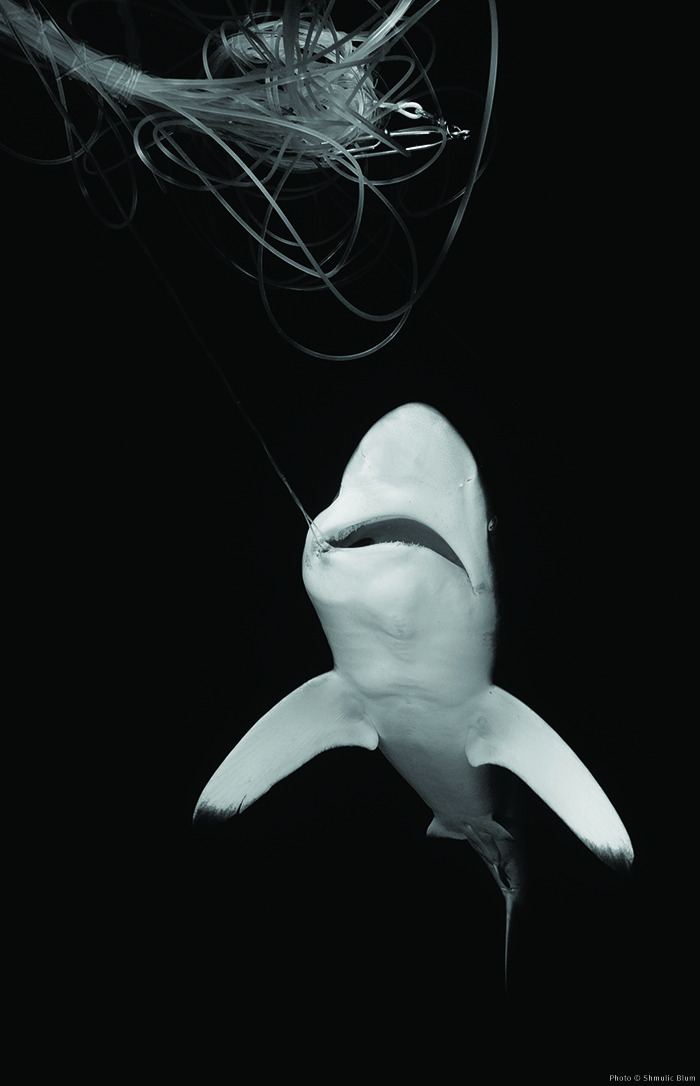

Unfortunately, shark aggregations are no secret to fishers who target them at these sites because of the high price their fins fetch in the international shark fin trade. Eastern Tropical Pacific shark populations have declined over 90 percent due to the overfishing for their fins, and sharks are not alone. Other highly migratory species like sea turtles that share the same biological traits as sharks, including being long-lived, maturing later in life, and producing few offspring, are caught under the guise of by-catch and suffer the same detrimental impacts due to their vulnerability to fisheries induced mortality.

Acknowledging the importance of protecting these sites from overfishing, the governments of Costa Rica, Colombia and Ecuador declared them national parks with respective no-take fishing zones. To further support these conservation efforts on an international diplomatic scale, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) declared the three islands as World Heritage Sites.

Since 2005, Migramar, a coalition of shark research institutions including non-government organisations and academia, has been generating the needed science in the Eastern Tropical Pacific to answer questions of the effectiveness of the no-take zones and propose an efficient conservation policy to decision makers. Migramar’s researchers now know that sharks only stay at aggregation sites temporarily, and that individuals move regularly from one island to another. The group also knows that larger no-take areas are necessary to protect these highly migratory species during their stay at aggregation sites, as some species, including endangered hammerhead sharks at Cocos Island, venture considerably beyond the 20-kilometre no-take area during nocturnal feeding excursions and are thus vulnerable to fisheries. Finally, Migramar experts know that after aggregating, many of these highly migratory species follow defined routes or “swimways” to other Shark Triangle islands.

Scientific evidence also shows that larger no-take areas lead to better protection of highly migratory species and as a result increase the profitability of fisheries in surrounding waters due to the spill-over effect. This case has been proven with tuna fisheries in waters surrounding the Galápagos Islands’ no-take zone.

Thus, saving Eastern Tropical Pacific sharks is not only going to take larger no-take zones in waters surrounding the islands of the Shark Triangle, it will also take policies that limit and control fisheries along these defined swimways. Migramar scientists are currently calling for the protection of the “Cocos Galápagos Swimway”, along the 700-kilometre submerged Cocos Ridge, a highly magnetic submerged mountain range, of which Cocos Island and the Galápagos Islands constitute summits that break the surface.

Fins Attached Marine Research and Conservation has been collaborating with Migramar members since 2005, and will continue to support not only the performance and publication of high quality science that answers these and other questions, but the regional political processes that will lead to science based policy and efficient protection for the sharks of the Shark Triangle.

Taken from Asian Diver Issue 1/2018