The Evolution of Freediving

With the constant innovation of diving gear enabling us to go deeper and longer underwater, it’s easy to forget that underwater diving began as a simple act of holding your breath and diving into the depths of the ocean. Read on as we trace the evolution of freediving from ancient times till now.

The Primordial Form of Underwater Diving

Mention underwater diving and images of compressed air tanks, air regulators, wet suits and snorkels inevitably come to mind. With the constant innovation of diving gear enabling us to go deeper and longer underwater, it’s easy to forget that underwater diving began as a simple act of holding your breath and diving into the depths of the ocean. Indeed, with the advent of modern underwater breathing apparatus, this most primordial form of diving now has to be differentiated from its more mainstream cousin by being renamed as freediving. Underwater360 reveals how underwater diving began more than 8,000 years ago and charts its evolution through the centuries to its present-day status as the extreme sport of competitive freediving that has been rising in popularity over the past three decades.

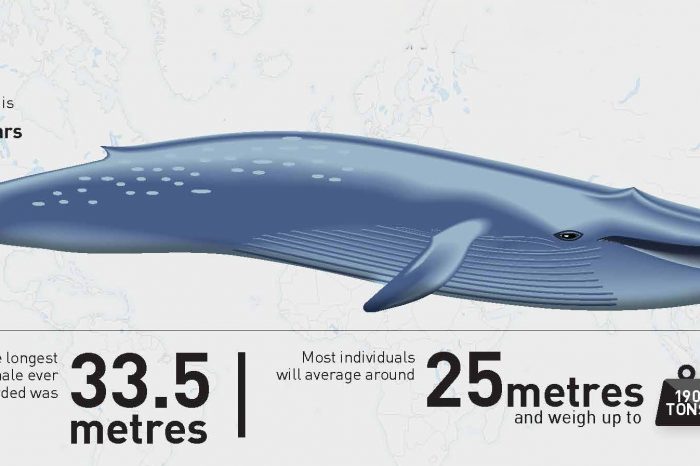

An illustration of Exostosis, or surfer’s ear, where the constant diving in water causes structural changes in the inner ear to occur.

Freediving in Ancient Times

The first recorded evidence of freediving humans can be traced back more than 7,000 years ago to the Chinchorro[1], an ancient people from 5,000 BC who lived along the coast of the Atacama Desert in what is present day northern Chile and southern Peru. In a study of Chinchorro mummies, archaeologists discovered that the bones of their ear canals had started to grow across the ear canal’s opening to protect their eardrums from recurrent exposure to water – a telltale sign of exostosis, a condition that afflicts people whose heads have been frequently dunked underwater. Exostosis is a common condition among people who surf, dive and kayak. The Chinchorro were a people who freedived for seafood. Shell midden fossils and bone chemistry tests on the mummies have proven that their diet consisted of 90 percent seafood. Besides the Chinchorro in South America, seashell fossils found in the coast of the Baltic Sea also revealed an ancient people living approximately 7,000 to 10,000 years ago who freedived for clams for sustenance.

Plato’s writing mentioned sponges being used in Greek bathhouses. Here we see a picture of Greek sponges harvested in from the Aegean.

Freediving in Ancient Egypt, Greece, Mesopotamia & Persia

There have been plenty of archaeological evidence of diving in Mesopotamia (West Asia – present day Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia) which dates back to 4,500 BC and in ancient Egypt in 3,200 BC.The Greeks have been freediving for more than 4,000 years. Artefacts and scripts from the Minoan civilization, which flourished from 2,700 BC to 1450 BC on Crete and other Aegean islands, include figures of seashells as well as colours produced by seashells in Minoan ceramic art. The Greek sponge trade can also be traced to as far back to Plato and Homer who mentioned the use of sponge for bathing in their writings. The Greeks would dive for sponges at Kalymnos island, using a skandalopetra (the Greek word for stone) like granite or marble weighing eight to 15 kilograms as a weight to descent quickly to up to 30 metres underwater to collect sponges. There is no exact date of when the Greeks started the sponge trade but Plato would have been 40 years of age at around 388 BC.

A sample of Minoan pottery illustrating their diving exploits

Divers have also been used by the Greeks in war. According to Thucydides, the famous Athenian general and historian who recounted the Peloponnesian War[2] (431– 404 BC) between the Delian League led by Athens and the Peloponnesian League led by Sparta until 411 BC, divers were used to infiltrate past underwater barricades that were set up to defend against invading ships. Messages would be relayed by these divers to allies or troops blocked by these barricades. These divers would also be used to scout the seabed for ship barricades to dismantle them.

The Persians have also been recorded to have used divers in warfare. Having conquered Phoenicia (now Lebanon) in 539 BC, King Cyrus the Great of the Archaemenid Empire used divers during the Siege of Tyre (now Lebanon) in 332 BC against Alexander the Great to cut the anchor cables of Alexander’s ships which were using battering rams against Tyrian defences.

Freediving in Sri Lanka (Ceylon)

For thousands of years, the Gulf of Mannar along India and Sri Lanka was known for the pearls and chanks (large spiral shells) harvested from the waters off Mannar island by Sri Lankan and Indian freedivers. According to the Mahawamsa, the historical chronicle of Sri Lanka, King Vijaya, a Kalinga (now Orissa, a state in India) Prince, landed in Sri Lanka in fifth century BC and sent a gift of a shell pearl worth twice a hundred thousand pieces of money to the Pandu King upon upon taking the hand of his daughter. The ancient Greeks, specifically Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador to the Mauryan royal court in India, also wrote in third century BC about the brilliance of the pearls from the island of the Taprobane in Sri Lanka. In ancient Greece, Sri Lanka was known as “Palaesimoundu”.

Literature from the Sangam-era (third century BC to fourth century AD) such as the Agananuru, an anthology collection of classical Tamil poetic work dated around the first and second century BC, talked about a community named Parathavar which fished but also dived for pearls and chanks. Arab traders and divers from the Persian Gulf also entered into the pearl fishery trade in Sri Lanka between seventh and 13th century AD.

Research shows that the divers would go out to sea in crews as large as 23 in a boat. On each boat would be a tindal or steersman, a saman oattee who was in charge of the boat, a thody who was tasked with bailing out water in addition to cleaning it, 10 divers including the adappanar or lead diver and 10 munducks or operational assistants who pulled up the oysters and the stone counterweights the diver uses while also pulling the divers up from the seabed into the boat.

The boats would go out late at night around midnight. The tindals (steersmen) would’ve started getting ready to hoist the sails more than an hour or so before with the adappanar (lead diver) hoisting a light at the masthead as a signal to set off. The divers in the boat would then get ready in the early hours of the morning by attaching the safety ropes around their waists which would be used to haul them up. Stones would also be tied to ropes to act as counterweights for the divers to do a fast descent to the seabed. As the ropes with the weights are released into the water, the diver would take a deep breath and descend rapidly by stepping on the weights. They would then start collecting oysters into the nets around their waists the moment they reached the seabed while the weights are pulled up into the boat. After about a minute, the diver would tug on the rope tied to him to signal the completion of his task, upon which he would be pulled upwards with the oysters he collected.

Ama: Freediving in Japan

The Ama(海人)are coastal people in Japan who make their living diving underwater to depths of up to 25 metres to harvest abalone, turban snails, oysters and pearls. Many ancient Japanese references[3] have stated that the Ama have existed for at least 2,000 years. One of the oldest references which refer to the Ama is the Gishi-Wajin-Den (魏志倭人伝) one of the oldest historical texts in Japan, which is believed to have been published in 268 BC. Some of the oldest archaeological evidence from Japan has shown that the Japanese have always depended on seabed resources. According to an ancient Chinese chronicle containing sporadic references to Japan, the northwestern part of what is now Kyushu has a lack of arable land to enable its people to survive on agriculture, which has compelled them to depend on the sea to barter for staples such as rice.

Woman Ama divers preparing to go to sea with their wooden barrels in tow.

According to Minoru Nukada from the Department of Health and Physical Education at Toho University[4], male and female Ama engage in different activities. Male Ama (海士) usually catch fish, either by hand or with a spear, whereas the female Ama (海女) will dive to the bottom of the seabed to collect seaweed and shellfish. Through time, the men engaged in off-shore fishing or became sailors on ships while the female Ama stayed at home and dived to supplement the farming harvest.

The Ama divers in Japan use a wooden barrel as a float.

Usually females, the Ama traditionally dive in only a fundoshi (loincloth) for ease of movement with only a tenugui (bandanna) covering their hair. These headscarves are sometimes adorned with symbols in order to bring luck to the diver and ward off evil. They also use a safety rope attached to a wooden tub or barrel that serves as a buoy which they can rest on in between dives. The barrel is also used to hold their catch. Their most important tool, however, was the tegane or kaigane – a spatula-like tool used to pry out abalone from between the rocks on the seabed. In the early 1900s, goggles were introduced and adopted by the Ama. In the decades after World War II, the Ama started wearing a white sheer garb for modesty while others started wearing rubber wetsuits in the 1960s.

There are various theories about why the Ama are mostly female. One is that the Japanese consider women to be more biologically capable of withstanding cold due to the distribution of fat in their bodies. They are also believed to be more adept at holding their breaths. The Ama are trained as early as 12 or 13 years old by elder Ama. At this stage of their training, they are known as Koisodo or Cachido and dive in shallow depths of only two or four metres from the beach. After they have been trained a few years (15 to 20 years old), they graduate to being Nakisodo, Okazuki or Funedo and are allowed to dive to four to seven metres in groups from a boat controlled by one or two boatmen who also act as watchmen for their safety. The Koisodo and the Nakaisodo both use the wooden tub as a buoy. A fully trained Ama is known as an Ooisodo, Okiama or Ookazuki. Usually more than 20 years old, the Ooisodo can dive to a depth of 10 to 25 metres and usually operate alone on a boat with a boatman for assistance. They use counterweights like a lead belt or a counterweight (haikara) connected to the boat with a rope and a pulley for a fast descent and are then pulled up quickly after harvesting the shellfish.

Hae-Nyeo: Freediving in Korea

Like the Ama of Japan, the Hae-Nyeo(해녀; 海女)or Jam-Nyeo are women freedivers who make their living from diving and harvesting shellfish and seaweed from the seabed. They are found in the southern part of the Korean Peninsula, especially Jeju island. Although the exact beginning of freediving in Korea is not known, Korean history experts agree that Jeju was the place where the Hae-Nyeo were first found. Historical records reveal that as early as 434 AD, pearls were found in the Shilla Kingdom.

A Korean Haenyeo diving in the sea collecting shellfish

It is not known when the men dropped out of the diving work. The only explanations we have is the physiological advantage that women have – greater subcutaneous fat and an ability to withstand the cold better.

The Haenyeo women freedivers in Korea operate out of Jeju Island.

Like their Japanese counterparts, the Hae-Nyeo start learning to freedive in shallow waters at age 11 or 12 and as their skill level progress, they graduate from being a lower level diver to intermediate and finally to an advanced level when they turn 17 or 18.

The Hae-Nyeo wear a black swimming trunk and a white cotton jacket. Diving goggles were introduced during the 1930s, with eye glasses used for almost two decades before diving face masks became available. They also use hollowed-out gourds around 12 inches in size as floats.

Sama-Bajau: Freediving in Southeast Asia

All freedivers are familiar with the “mammalian dive response” – when your heart slows down, blood vessels constrict and your spleen contracts because your body is trying to keep you alive while you are holding your breath underwater. For the Sama-Bajau – a group of sea nomads of Austronesian ethnic group from Southeast Asia who live off the sea in waters around the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia and Borneo – a study about human hypoxia tolerance published by the journal Cell[5] has revealed that a genetic DNA mutation has given them larger spleens which allows them to be able to freedive underwater to harvest shellfish and food at depths of up to 60 metres for as long as 13 minutes.

Sama Bajau are nomads who have an unnaturally large spleen which allow them to hold their breaths for up to 13 minutes at a time.

In the human body, the spleen recycles red blood cells and helps to support your immune system. After previous studies revealed that diving mammals like elephant seals, otters and whales have disproportionately large spleens, Melissa Llardo, the author of the hypoxia study in Cell was eager to find out if the same was true in humans. Her studies revealed that the median size of the spleen of a Sama-Bajau person was 50% larger than that of the Saluan people, a related group of people on the Indonesian mainland. The Sama-Bajau also had a gene called PDE10A (which the Saluan did not have) that is thought to control a certain thyroid hormone that in mice is known to be linked to spleen size.

Modern Freediving

The Legend of 1913

Most freedivers cite the legendary retrieval of the missing anchor of the Italian navy ship, Reggina Margherita, by a Greek sponge diver on 16 July 1913, from an estimated depth of about 88 metres underwater, as the first incidence of modern freediving. While the exact name of this Greek sponge diver has varied from Stotti Georghios, Stathis Hatzis, Stathis Chatzi to Haggi Statti and Chatzistathis, what is not in dispute was his pulmonary emphysema, his perforated eardrum from years of diving without proper equalization and the fact that he tied a safety rope to his waist and proceeded to descend quickly to the seabed using the primitive Greek “Skandalopetra” method of holding onto a giant rock as a counterweight. He is also consistently described as being a man of average height (1.7 metres), weight (65 kilograms) and age (35 years old). And it is unanimously agreed that he successfully retrieved the anchor by freediving and was rewarded for his efforts with £5 and the lifelong permission to fish with dynamite.

The Race to the Bottom Begins

In the years after the legend of 1913 grew, freediving started to evolve as a sport with some notable people setting and breaking records as the motivation to be record breakers in freediving led to divers developing techniques and discovering natural physiological responses like blood cooling, our diving reflex and blood cooling among others.

Freediving Tools Take Shape

- In 1927 Jacques O’Marchal invented the first diving face mask that enclosed the nose.

- In 1933, Louis de Corlieu patented fins you could wear on your feet. Calling them “swimming propellers” they were later mass produced by Owen Churchill, an American

- In 1938, Maxime Forjot improved upon O’Marchal’s design by using a compressible rubber pouch to cover the wearer’s nose, thus enabling divers to pinch their nostrils shut to make it easier to equalise the pressure in the ears

- Britain and the United States purchased huge quantities of Owen Churchill’s flippers during World War II

- In 1951, Hugh Bradner, diver and physics student came up with the first diving wetsuit made out of neoprene, which the US Navy snapped up for US Marines in the Korean War

Competitive Freediving Begins

Like the one-minute mile, the 30-metre freediving mark was an important milestone that kickstarted the modern competitive freediving movement. Although scientists had openly predicted pressure-crushing death at that depth, in 1949, the era of Italian domination of competitive freediving kicked off in earnest when Raimondo Bucher, an Italian air force captain (and an avid spear fisher) born in Hungary, officially became the first man to dive to a depth of 30 metres. Using a large rock as a counterweight, Bucher dived to the bottom of the sea at Naples without breathing apparatus. He was met at that target depth by Ennio Falco, a fellow Italian diver, who had staked 50,000 lire against him completing the feat. Bucher won the 50,000 lire but Falco would take his record two years later.

The Italian Job

Bucher’s freediving record fired up the competitive freediving scene in Italy and the next two decades saw the Italians dominate the freediving record books with freediving legends like Alberto Novelli and Enzo Maiorca spearheading the sport of deep freediving. Together with Brazilian freediving Americo Santarelli (who retired in 1963) and later Jacques Maol, the famous French freediver who used yoga techniques and mediation to calm his body, freediving records were taken to ever greater depths. Mayol would achieve 11 world records and was the first freediver to go past 100 metres. Despite the fears of scientists who believed that high pressure in deep depths would collapse human lungs, Enzo Maiorca broke the 50 metre barrier in 1962 and would go on to achieve 17 world records. Maiorca and Mayol’s rivalry was immortalised in Luc Besson’s 1988 film, The Big Blue, a fictionalised take on the two freedivers’ rivalry. Angela Bandini of Italy would shock the freediving community in 1989 by become the first human to freedive to 107 metres underwater, breaking Mayol’s world record by two metres.[/vc_column_text]

In the 1960s, women freedivers such as Gilliana Treleani (Italy) and Evelyn Patterson (Great Britain) had flown the flag successfully for women freedivers by diving deeper than 30 metres. Treleani achieved the mark of 35 metres in 1965. Constant Weight Apnea, one of the three disciplines of freediving recognized by AIDA was pioneered by women freedivers Francesca Borra and Hedy Roessler, both from Italy in 1978. [Constant Weight Apnea (CWT) is a freediving discipline whereby a freediver descends and ascends with the help of their fins or monofin and/or their arms without pulling on the rope or changing their ballast. Only a single hold of the rope, either to stop the descent of start the ascent is allowed] During the 1980s, Enzo Maioca’s two daughters, Patricia and Rossana Maiorca were also responsible for furthering women’s freediving as Patricia freedived to 70 metres while Rossana freedived to 80 metres.

Modern Freediving in USA

One of the pioneers of freediving in the United States is Robert Croft, a US Navy diving instructor who taught navy personnel how to escape from a stricken submarine. Croft could hold his break for more than six minutes and was studied by US Navy scientists for signs of “blood shift”. Croft set three depth records in a one-and-a-half-year period and in 1967, he overcame what scientists believed to be the human physiological depth limit for freediving by becoming the first person to dive deeper than 64 metres. Croft also developed the Glossopharyngeal Breathing Technique, a technique of forcing more air into your lungs before a dive called lung packing. He would go on to become to first freediver to dive beyond 70 metres by achieving a freediving depth of 73 metres before retiring from competitive freediving in 1968.

The flagbearer for US freediving after Croft is Tanya Streeter. Streeter reached 113 metres with a No Limits dive in 1998. She broke world record that surpassed the men’s apnea record with a No Limits dive of 160 metres in 2003 and a Variable Weight record of 122 metres that lasted for seven years.

No Limit Freediving

With the retirement of Mayol and Maiorca, a new freediving rilvary was born with Italian Umberto Pelizzari and Cuban Francisco Rodriguez (better known as Pipin Ferreras) both appearing on the scene around 1990. With advent of new freediving disciplines such as Constant Weight and Variable Weight Apnea (a discipline where the freediver descends with the help of a counterweight and ascends using his own strength, either by pulling or not pulling the rope), the traditional form of freediving, i.e to dive as deep as possible on one breath, going down with weights and coming up with a buoyancy bag, was now renamed as No Limit. Pelizzari and Rodriguez pushed No Limit Apnea to new depths, going to 110, 120 and 130 metres and beyond. The current no limits world record holder is Herbert Nitsch who dived to 214 metres on June 14 2007 in Spetses, Greece. An Austrian freediver, Nitsch has held 32 world freediving records across every freediving discipline.

The Founding of AIDA

Freediving continued to grow and develop internationally in the 1980s and 90s and in 1992, the Association Internationale pour le Developpement del’Apnée (AIDA) was founded by Frenchmen Roland Specker, Loic Leferme and Claude Chapuis in Nice, France, with Specker serving as its first President. Set up to organise clinics to grow the sport of competitive diving, the International Association for Development of Apnea, aka AIDA, is the worldwide body responsible for keeping the records and rules of competitive freediving events worldwide. AIDA establishes the safety standards and the ratification of official freediving world record attempts and freediving education. AIDA International is the parent organization for national clubs of the same name.

Besides Constant Weight, Variable Weight and No Limit Apnea, another discipline of freediving that has captured the public’s imagination is Static Apnea, which measures how long a person can hold their breath (apnea) without swimming any distance. The current record for Static Apnea is held by Aleix Segura Vendrell, who set a record of 24 min 3sec on February 28, 2016.

Iconic Modern Freedivers

One of the most iconic freedivers who was considered as “possibly the world’s greatest freediver” was Natalia Molchanova. A Russion champion freediver, Natalia was the most decorated freediver at the time of her death. She was the holder of 41 world records and had won 23 gold medals when she went missing on 2 August 2015 while giving a private dive lesson near Ibiza, Spain. The first woman to go past 100 metres (she freedived to 101 metres in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt) while freediving with constant weight, Natalia could hold her breath for nine minutes. On the fateful of her accident, she had dived to about 40 metres in Ibiza, and was believed to have been caught by a current and never resurfaced.

Her son Alexey Molchanov is the current world record holder in the constant weight apnea category for men with a world record of 130 metres achieved in 3 min 55 sec.

[1] Arriaza, Bernardo T. Beyond Death: The Chinchorro Mummies of Ancient Chile. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1995. Print.

[2] Thucydides (2009) [431 BCE]. History of the Peloponnesian War. Translated by Crawley, Richard.

[3] Rahn, H.; Yokoyama, T. (1965). Physiology of Breath-Hold Diving and the Ama of Japan. United States: National Academy of Sciences – National Research Council. p. 369. ISBN 0-309-01341-0. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

[4] Ibid, pg 25[

[5] Cell journal at www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(18)30386-6_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS0092867418303866%3Fshowall%3Dtrue