Diving the Great Basses

Join diver extraordinaire Dharshana Jayawardena as he takes on the massive waves and surge of the renowned Great Basses in Sri Lanka

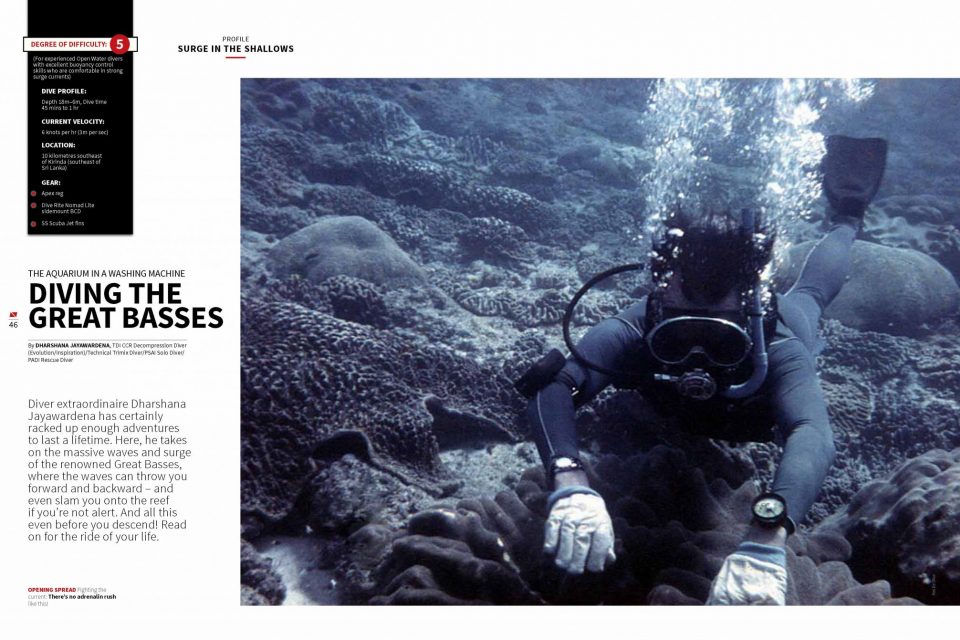

Diver extraordinaire Dharshana Jayawardena has certainly racked up enough adventures to last a lifetime. Here, he takes on the massive waves and surge of the renowned Great Basses, where the waves can throw you forward and backward – and even slam you onto the reef if you’re not alert. And all this even before you descend! Read on for the ride of your life.

I AM AT a unique, strange, fearsome, wonderful place.

Towering in front of me, like a rocket ship about to be launched to the stars, is a gleaming white lighthouse 37 metres high. The strangeness comes from the fact that I am 12 kilometres southeast from the coast of Sri Lanka (latter day Ceylon); far out at sea and in the middle of nowhere, where no lighthouse should be.

Yet, there is a good reason for the existence of this lighthouse. As I watch in awe, and with a mild sense of fear, a massive wave crashes around the base of the lighthouse with a reverberating boom. Am I really supposed to dive beneath this? This explosion of surf is followed by white foam that starts breaking along an invisible line that runs for hundreds of metres to the west of the lighthouse. It betrays the presence of a arge monster lurking just beneath the surface of the ocean.

It is the Basses Reef.

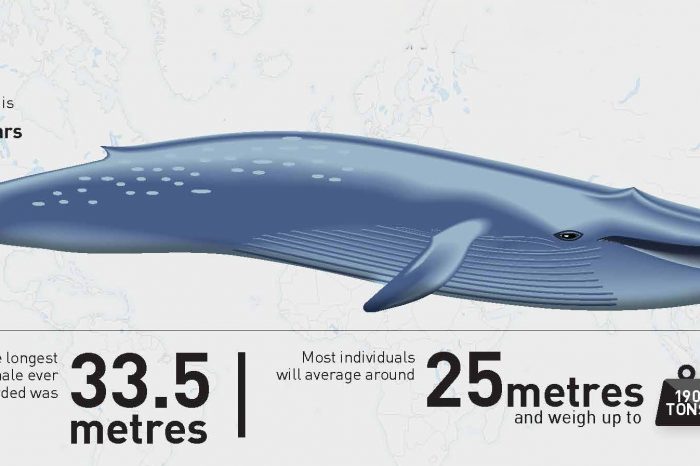

The word “Basses”, derived from the Portuguese term for reef, baixios, is an approximately 40-kilometre-long underwater limestone geological formation. The areas surrounding two high points on this reef are known as the Great Basses Reef and the Little Basses Reef. These high points barely breach the surface and proved to be a curse for ancient mariners navigating the waters around the coast of Sri Lanka. All shipping from east to west and vice versa had to pass below the coast of Sri Lanka and for centuries, this mid-ocean reef claimed dozens of ships and hundreds of lives, forcing the British occupiers of Ceylon in the late 19th century to build two lighthouses to safeguard maritime commerce.

The Great Basses lighthouse was built in 1873 and the smaller Little Basses lighthouse, five years later.

The magnificent offshore lighthouse at Great Basses Reef (Photo by Dharshana Jayawardena)

Today, these two lighthouses are among the most famous offshore lighthouses in Asia. In the 1960s, moviemaker Mike Wilson and world famous science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke discovered the remains of an ancient Mughal ship just by the Great Basses Lighthouse. In the obliterated shipwreck were not only cannons and anchors but also tons of “Surat” silver coins belonging to the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb (1658–1707), son of the great Shah Jehan, who built the Taj Mahal in Agra, India. This discovery and early diving attempts at the Great Basses is brilliantly chronicled in the book, Treasure of the Great Reef, by Clarke and is a must-read for all divers before diving the Basses.

Beautiful as the view above the surface is, the true wonders of this place lie beneath, making this one of the most sought-after locations for diving in Sri Lanka. Even though the dives are relatively shallow, from a depth of 18 metres to 3 metres, only experienced divers comfortable in strong current and surge conditions should attempt this dive. In fact, the shallower it gets, the more dangerous the dive becomes, because you can get smashed on the top of the reef.

A giant trevally swimming just near the Basses Ridge, as a wave breaks over (Photo by Dharshana Jayawardena)

Access to Great Basses is from Kirinda, a small fishing town in southeast Sri Lanka located near the famous Yala National Park, an area with one of the highest densities of leopards in the world. Kirinda is also as remote as it gets from Colombo, the financial capital of Sri Lanka. There are no dive centres here, but centres around Galle run regular expeditions as well as expeditions on request, during a small window of opportunity in which Basses can be dived. This is because the reef is virtually unreachable during the two Sri Lankan monsoon seasons.

It is mostly dived during mid-March to mid-April when the conditions can be at their best during the brief inter-monsoon period. Even then, the constant battering of huge waves on the reef will cause fierce currents. Also, in the afternoon, the wind can pick up, making the surface conditions rough.

The boatman expertly navigates the boat around the surf and positions it just a few metres south of a jagged rock. We are about 20 metres away from the lighthouse. I roll back into the foamy water with a splash and quickly swim to the bottom as fast as I can to avoid getting slammed onto the reef by an oncoming wave. At the bottom, I’m greeted by a startling visual panorama. All around me are magnificent forms and shapes made of limestone; carved over eons by the relentless wave action. Some are caves and swim-throughs. Some are grotesque geological deformities, and for a moment, they deceive me into thinking that I am in a distant and hostile planet.

The water is crystal clear. The sand at the bottom is a mixture of limestone grain and various seashells. It is furrowed into countless ridges by the constant surge action. The currents billow over the small ridges, like the wind creating a temporary cloud of dust and debris that soon clears up.

The Great Basses Location: Spanning almost 40 Km and being the last frontier against the merciless forces of a massive ocean, which only ends at the frigid wastelands of Antartica, this is the magnificent Basses Ridge, the great barrier reef of Sri Lanka

And the current is strong!

For the uninitiated Basses diver, the first dive can be an unnerving experience. You are literally thrust four to six metres forward and then after a very brief lull, shoved backward. At the same time, you have to avoid obstructive limestone formations and watch your head. It is quite funny to see a shoal of fish in the same body of water, as you move forward and backward. This is a great place to see fish go backwards!

Swimming in this environment and getting close to the reef is a constant battle. You move with the forward surge and as you are sucked backward, try to hold position by finning vigorously. Then dash forward and again hold position, and then again dash forward. Some of the limestone formations are narrow gullies and caves. Great care must be taken when entering these. You have to take it one step at a time – study the current, watch the movement of marine life and be prepared to turn back if you think it is going to be tricky.

It is easy to get lost in the maze and not be able to find your way to deep water away from the reef. Surfacing near the reef is the last thing you want to do, and one rule of thumb is to ensure that your depth is always below six metres. If you do get sucked up towards the surface, you must immediately turn head down and fins up, and propel like crazy towards the bottom away from the upward surge.

Read the rest of this article in 2015 Issue 3 Volume 138 of Asian Diver magazine by subscribing here or check out all of our publications here.