Pioneer of the Week: Louis Boutan

This week we pay tribute to one of the world’s first underwater photographers, Frenchman Louis Boutan.

Although records date the first underwater photograph to have been taken in 1856 by William Thompson and a Mr Kenyon, who used a pole mounted camera, the world’s first supposed official underwater photographer began his work in 1893.

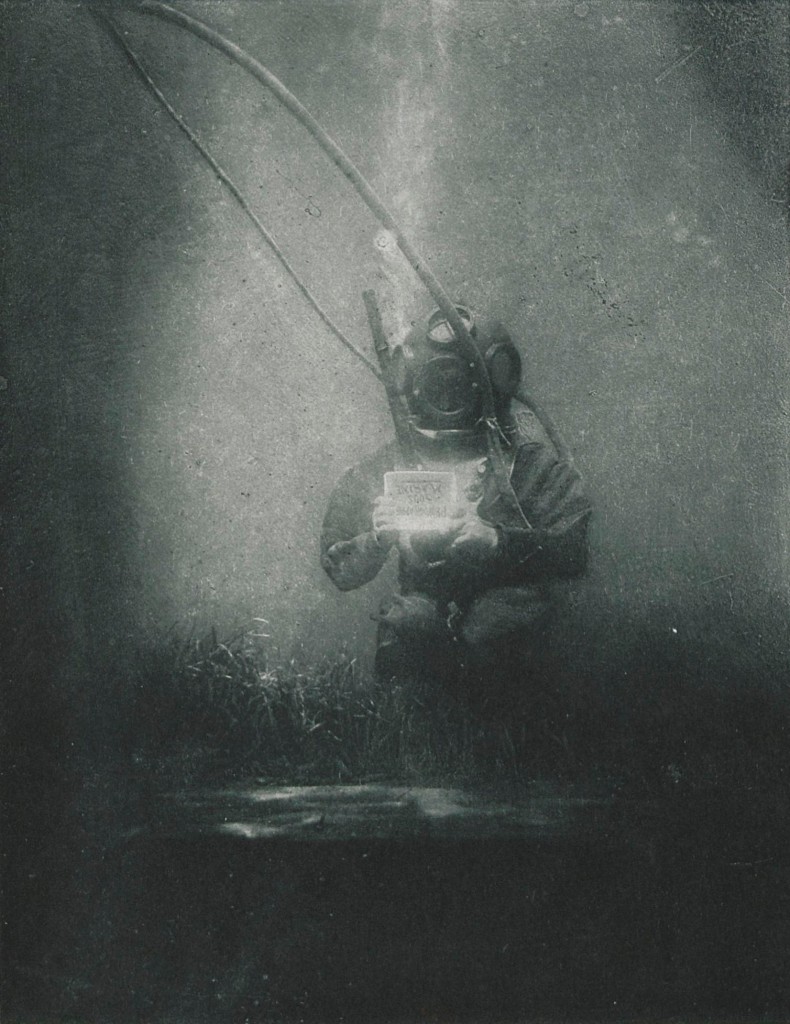

One of the first underwater shots, Louis Boutan. © Wikimedia Commons

Boutan was first interested in biology, graduating in 1879 with a Doctorate of Science from the University of Paris. In 1893, he became a professor at the University’s marine biology lab: Arago Laboratories at Banyuls-Sur-Mer. His work brought a new perspective on the world beneath the waves, and he even got the chance to dive. After encountering untouched underwater landscapes up close, Boutan was inspired to find a way of capturing them and bringing what he saw to the surface.

To create his concept of capturing underwater photographs, he contacted his brother Auguste. Auguste was an engineer and drafted a plan for an underwater camera that allowed for underwater adjustments to the diaphragm, plates, and shutter. The first design even included a method of changing the buoyancy of the camera through an air-filled balloon. That same year, the camera was built and Louis began to experiment.

Like many first-time experiments, he was left disappointed. The lighting wasn’t what he had expected. Until this point, flash photography required oxygen; typically utilising burning magnesium or a mixture thereof. Within the same year, electrical engineer M. Chaffour helped Boutan create a bulb to house a magnesium ribbon. The bulb was filled with pure oxygen and the magnesium ribbon was lit using an electric current. Unfortunately, the burning magnesium led to a thick smoke of magnesium oxide, which lightly coated the inside of the bulb and dimmed the images. It was also a hazard, as bulbs would explode from overheating.

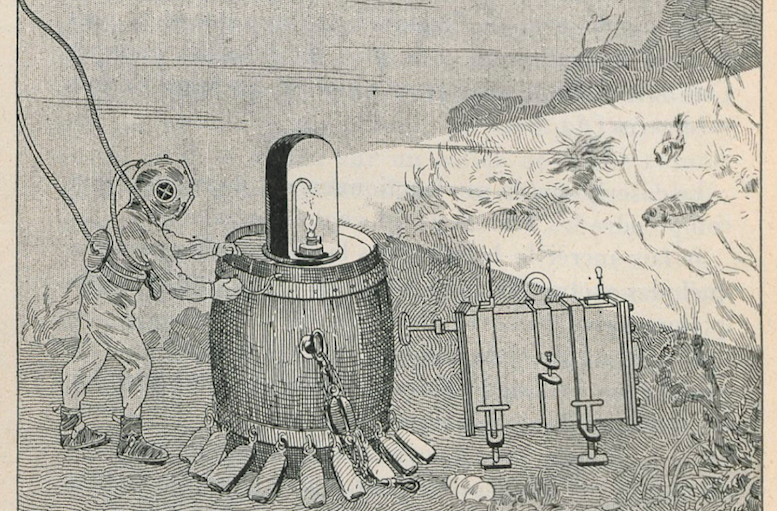

With the failure of the first bulb, Boutan’s assistant, Joseph David, helped create a more reliable flashbulb – one that wouldn’t explode in his face. This new flash used a rubber bulb that blew magnesium powder in a burning alcohol lamp. While this method was more reliable, it had to be attached to a wooden barrel and was therefore extremely inconvenient and hardly portable – really, who could catch the dynamic dance of a sailfish with a camera fastened to a beer barrel?

A diagram showing how underwater photographs could be taken using magnesium light © Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Département des Estampes et de la Photographie

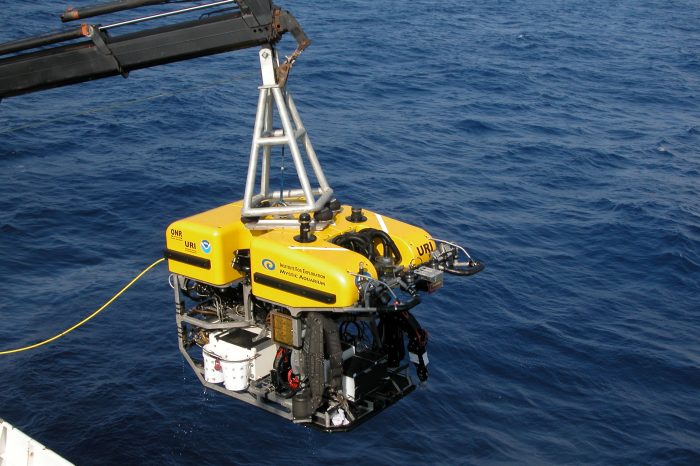

Instantly, Boutan began to develop more reliable methods of photography – more-compact and more-portable flashes, smaller camera boxes, and improved lenses. Eventually, they produced a smaller design of the camera box, small enough to be lost in seaweed when dropped and able to be lowered to the seafloor by hand. In addition to easier manoeuvrability of the camera, Boutan began to use a system of dual, carbon-arc (electricity) lamps.

After further experimentation, Boutan became one of the principal – and perhaps one of the only – underwater photographers of his time. In 1898 he published a book detailing his work with underwater photography titled La Photographie Sous-Marine (Underwater Photography). He included several of his illustrations in the book, plus many photos that he had taken over the years.