Saving Tubbataha’s Tiger Sharks

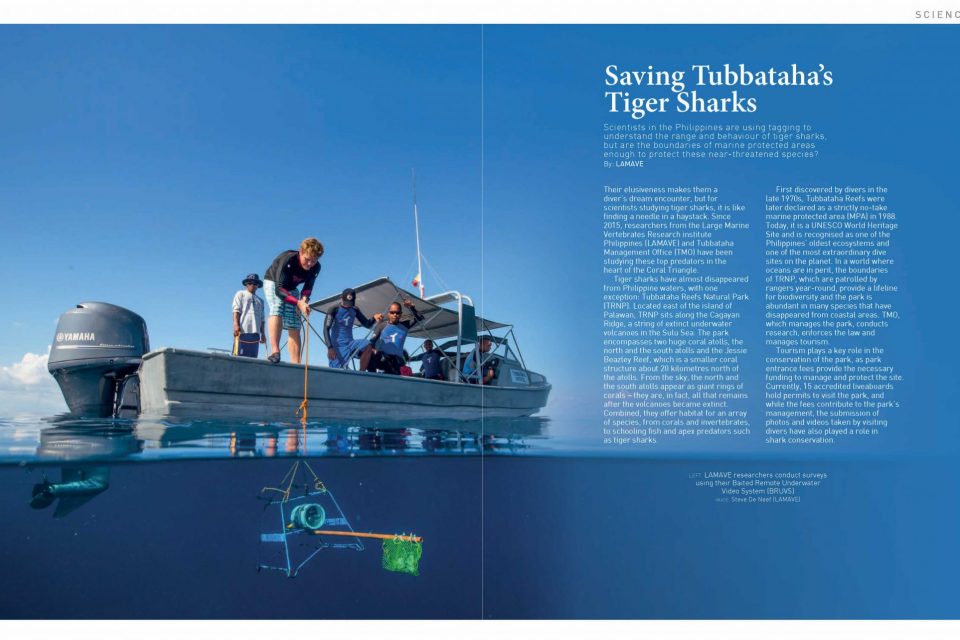

Scientists in the Philippines are using tagging to understand the range and behaviour of tiger sharks, but are the boundaries of marine protected areas enough to protect these near-threatened species? Read on as LAMAVE reseachers investigate [Text by Large Marine Vertebrates Research Institute Philippines (LAMAVE). Image by Steve De Neef]

Their elusiveness makes them a diver’s dream encounter, but for scientists studying tiger sharks, it is like finding a needle in a haystack. Since 2015, researchers from the Large Marine Vertebrates Research institute Philippines (LAMAVE) and Tubbataha Management Office (TMO) have been studying these top predators in the heart of the Coral Triangle.

Tiger sharks have almost disappeared from Philippine waters, with one exception: Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park (TRNP). Located east of the island of Palawan, TRNP sits along the Cagayan Ridge, a string of extinct underwater volcanoes in the Sulu Sea. The park encompasses two huge coral atolls, the north and the south atolls and the Jessie Beazley Reef, which is a smaller coral structure about 20 kilometres north of the atolls. From the sky, the north and the south atolls appear as giant rings of corals – they are, in fact, all that remains after the volcanoes became extinct. Combined, they offer habitat for an array of species, from corals and invertebrates, to schooling fish and apex predators such as tiger sharks.

First discovered by divers in the late 1970s, Tubbataha Reefs were later declared as a strictly no-take marine protected area (MPA) in 1988. Today, it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is recognised as one of the Philippines’ oldest ecosystems and one of the most extraordinary dive sites on the planet. In a world where oceans are in peril, the boundaries of TRNP, which are patrolled by rangers year-round, provide a lifeline for biodiversity and the park is abundant in many species that have disappeared from coastal areas. TMO, which manages the park, conducts research, enforces the law and manages tourism.

Tourism plays a key role in the conservation of the park, as park entrance fees provide the necessary funding to manage and protect the site. Currently, 15 accredited liveaboards hold permits to visit the park, and while the fees contribute to the park’s management, the submission of photos and videos taken by visiting divers have also played a role in shark conservation.

TUBBATAHA’S SHARKS

Before 2015, only a few studies had been carried out to investigate the sharks present in the park. In March 2015, as part of an effort to confirm all shark species in TRNP, researchers from LAMAVE in collaboration with TMO made a call out to dive boats for shark encounters captured in images or on video. LAMAVE has been operating in the Philippines since 2010 and today it is the largest independent non-profit non-governmental organisation dedicated to the conservation of marine megafauna and their habitats in the Philippines. The collaboration between LAMAVE and TMO is currently the biggest shark study in the country.

While photos sent in by divers provided vital information for establishing past tiger shark encounters, LAMAVE researcher Ryan Murray went to live on the TRNP ranger station and, together with the rangers, set about rigging the park with underwater cameras to see what shark species were present and in what numbers. Submissions from divers revealed chance encounters with tiger sharks within the recreational diving range, whilst the remote video cameras, which are mounted on a metal frame and lowered into the water by the team, allowed the collection of information down to 100 metres, revealing a new perspective of the park.

At least five different individual tiger sharks have been identified (by their first dorsal fin) from photos and videos submitted by visiting divers. While this established the presence of tiger sharks in TRNP, it did not reveal how they were using the park, and more importantly, if the sharks were moving outside its protected boundaries. Previous research has shown that tiger sharks are capable of making large scale movements; one study showed a tiger shark crossing the Atlantic Ocean, travelling 6,500 kilometres from northeastern US to the western coast of Africa. Another study by a research team in Western Australia tracked a female tiger shark over 4,000 kilometres between Ningaloo Reef in Western Australia and Sumba Island, Indonesia. Long-distance movements have implications for the management and protection of tiger sharks, as sharks initially encountered in protected areas could be exposed to fisheries outside protected waters, and TRNP is no exception.

The park is the most successful marine protected area in the Philippines and is the country’s largest strictly no-take zone, covering 97,030 hectares – an area larger than Singapore (which is under 75,000 hectares). That’s very impressive, but when we take into consideration that some tiger sharks travel thousands of kilometres, and the fact that at its widest, TRNP stretches around 50 kilometres, it would not be a surprise if sharks moved beyond the boundaries of the park. Still, a rich environment like TRNP may decrease the desire to roam, depending on how the sharks are using the area.

To find out more, LAMAVE and TMO took two approaches: First, the team deployed satellite tags to find out where the sharks were going; they also used acoustic tags to understand how they were using the park.

TAGGING TIGERS

In May 2016, TMO and LAMAVE researchers successfully tagged the first tiger shark in the Coral Triangle: A 3.4-metre female was fitted with an ARGOS-transmitting dorsal fin-mounted satellite tag. The team tagged a second tiger shark in 2017. These tags have a small antenna and a wet/dry switch that is triggered when it breaks the surface.The tag interacts with passing ARGOS-system satellites, and when both the tag and satellite align, location and temperature data is transmitted. A successful transmission results in an email disclosing the location of the shark and whether the individual is inside or outside the boundary of the park.

However, the technology is not without its challenges and the shark’s position is only reported when the tag breaks the surface, a limitation when working with sharks, as unlike marine mammals, they do not need to break the surface. As a result, transmissions can be few and far between, offering only few, or no clear conclusions.

To date, 20 animals encountered in the park have been fitted with acoustic tags: two tiger sharks, 14 grey reef sharks, and four reef manta rays. The research is ongoing and many of the tags will last up to 10 years. New acoustic receivers are being placed in the park, which will help build a more detailed map of the animals’ movements. The team will also expand the acoustic network in 2018 deploying receivers in the waters of Cagayancillo, an archipelagic municipality located around 130 kilometres northeast of TRNP.

While acoustic data collection is ongoing, preliminary results from the satellite tags have shown that at least one of the tagged tiger sharks has ventured beyond the boundaries of TRNP – a worrying prospect, as tiger sharks do not enjoy general protections in Philippine waters. On August 8, 2017, the Philippine Navy seized 10 Vietnamese nationals aboard a fishing vessel intercepted in northwest Palawan; they were carrying around 70 sharks, including tiger sharks. Two days later, poaching charges were filed against them. While the fishing vessel was intercepted approximately 350 kilometres north of TRNP and had not entered the park, it is clear that sharks outside TRNP are in danger from illegal and unreported fisheries.

Read the rest of this article in 2018 Issue 1 Volume 149 of Scuba Diver magazine by subscribing here or check out all of our publications here.